Two Dances, New York City: 1935, 2015

1935

In 1935 Anna Sokolow’s company the Dance Unit performed A Strange American Funeral for the first time at the New Dance League’s third festival in New York City. The event was organised to showcase a cross section of dance troupes that operated around the American branch of the Communist Party, from amature hobbyists to full-time professional dancers.

Appearing late on in the sequence of performances, alongside the other professional acts, Sokolow presented her choreography with a specially composed score by Elie Siegmeister and a reading of a poem by Michael Gold, from which the performance took its name. [1]

Gold’s original poem, A Strange American Funeral at Braddock (1924), was written as an eulogy for Jan Clepak, a Pennsylvania steel worker who perished in a vat of molten iron ore. [2] No trace of Clepak could be found after the accident, his skin, hair and bones were dissolved by the liquid metal and integrated into its compound. A lump of iron was offered to Clepak’s widow for the funeral to give weight to the coffin: an equivalent mass of metal in exchange for his transmuted flesh. [3]

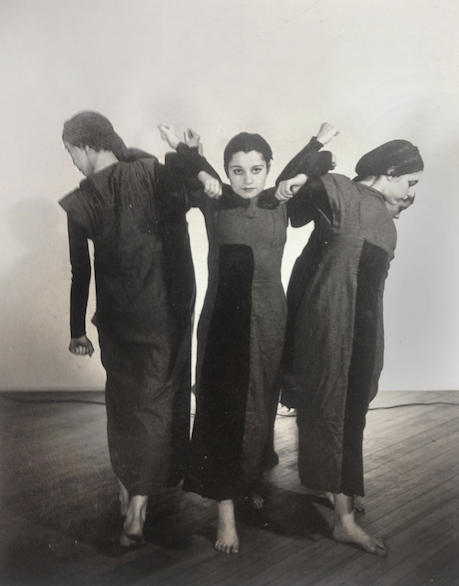

Figure 1) Unknown photograph, presumably of the Unit rehearsing A Strange American Funeral. Joseph North and Helen Oken North Family Papers: Series I: Joseph and Helen Oken North Papers (Records and Memorabilia) Anna Sokolow Posters and Programs (Undated) Tamiment Library & Wagner Labor Archives, TAM.605, Box: 8, Folder: 14. New York University, New York.

As the words of the poem were read out, Anna Sokolow’s dancers restaged Clepak’s alchemic transformation through their bodies; their motions mutated throughout the performance, theatricalising the metamorphosis by juxtaposing solid steel blocks of dancers with soft, sensual movements. [4]

Accounts written after the performance attest to this continued transition between turgid and flaccid forms as the choreography’s structuring principal. [5] Notable, it seems, is that this transformation did not happen only once as in the poem - from flesh to steel - but rather recurred, constructing a rhythmic refrain of transformation and re-transformation between different material states. [6]

The jarring, anti-narrative choreography made no attempt to act out or visualise the anthemic narrative of the poem, nor did it follow the rhythms dictated by the song, but rather, as critic Leonard Dal Negro noted in his 1935 review of the performance in New Theatre, presented “sharply stylised [and] aggressive [movements]…designed free and independent” of the formal dictates of its theatrical accompaniments. [7]

Task like actions were performed and repeated; mime-like gestures undertaken: hands clasped, feet scuttled and torsos stiffened, reminding the viewer of absent tools and levers, absent places of work and transit. Those same bodies that did work also became the material on which that labour was performed: human bodies became the molten steel, the architecture of the factory, the mechanisms of machinery and the processes of production. These invocations of industry were intersected by the softer movements, the gentle gestures that punctuated the dance; such intimate moments were presented as just another in a sequence that had capitulated to the logic of transition.

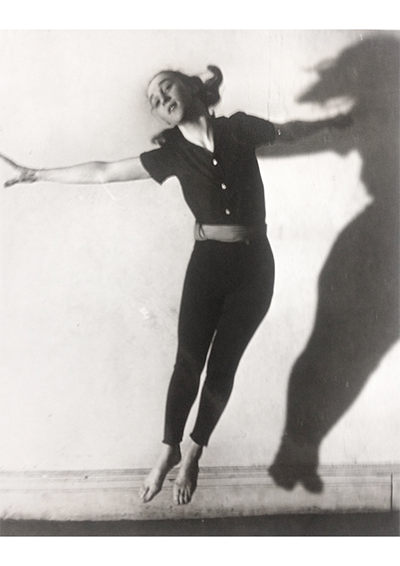

Figure 2) Unknown photograph of Anna Sokolow Joseph North and Helen Oken North Family Papers: Series I: Joseph and Helen Oken North Papers (Records and Memorabilia) Anna Sokolow Posters and Programs (Undated) Tamiment Library & Wagner Labor Archives, TAM.605, Box: 8, Folder: 14. New York University, New York.

The basic choreographic structure consisted of three different formal components: the dance, the score and the reading. The poem and the score were not made to appear with dance, but rather were appropriated by Sokolow and embedded, montage like, into her performance. [8] Held together by only the durational structure of the performance, these three different interpretations of Clepak’s death were collapsed into the same space and time, but not into the same register. The discordant combination of three distinct interpretations presented the dancing body as a collection of fragmentary experiences, gathered inharmoniously, circulating with each other as incongruous environmental elements.

Rather than utilising performance as a kind of drill for what the ‘return’ or ‘rediscovery’ of a socialist awakening could be, Sokolow established the performance as a sequence that addressed repetition and transition. [10] The body of Jan Clapek was distributed across the women’s figures, as they flexed and contorted, forming and un-forming his violent death, with metal and soft flesh so entwined that end of one and the beginning of the next was indeterminable.

As the cycles of violence repeated, Clapek’s specific body receded, becoming an elemental figure in a greater procession of people and things. The ubiquity of violence and production became the process through which these dancing figures appear – the transitional state of the choreography as it clashed with the rallying words of the poem and the staccato composition framed arbitrary moments of relief, only to dispel them again through jarring asymmetry. Clapek’s body then, like the dancers own bodies, sat in a discontinuous temporal space, unable to be communicated as separate from the technological mechanisms that brought about his ultimate demise. The cooperative movements of the women’s bodies, as they danced, repeating well-rehearsed gestures, was always locked, inextricably, with the exploitation of that capacity through industrialisation. [9] Bodies in A Strange American Funeral are shapely only in moments: done and undone by violence, forged through steel and architectural vignettes.

***

When looking through some of the programme notes of Anna Sokolow’s longer performances during the 1930s a similar investment in interlaying seemingly disparate material and mediums is evident through the construction of her recitals.

One undated recital from the late 1930s is set in five distinctive acts. [10] It begins with a dance performed over a reading of a poem by the Soviet War poet Konstain Simonov, leading into a solo by Sokolow over a composition by long time musical collaborator Alex North called Madrid 1937. Next, a poem called Mama Beautiful by Mike Quin, featured as a two-part performance followed by Sokolow’s Case History No. -, the title of which is subhead with a quote from the Juvenile court records, outlining the socio-behavioural ‘types’ that are destined for prison. Richard Wrights Between the World and Me is then read, followed by another solo by Sokolow titled Lament for the Death of a Bull Fighter and finally, to the penultimate performance, Songs of a Semite, where a reading of Lamentations 1, 12 was read before the concluding dance The Exile.

In this programme, like in A Strange American Funeral, disparate and jarring elements are thrown into calculated relation. From Russian war laments, to self fulfilling prophecies of Juvenile Court Records, to Wright’s painful, complex meditation on the collective experience of lynching, to the continued importance of ancient Jewish knowledge. These elements remain stuccoed and decontextualized in the event, never forced into a narrative or a specific subject position; they hang, related by Sokolow’s sequence, as remnants.

In their hanging together as remnants the power of their collective address is amplified: the interconnectedness of seemingly distant histories is brought together through the idea of the residual. What binds these fragments in the greater structure is their status as waste: Simonov’s poem as the waste product of war; the body of Case Study No. - the waste product of policy designed to ensure poverty and incarceration; the poetry of the collective pain and endurance of black communities in the United as the waste product of the global slave trade; the dancing body as the waste product of the capacities of human energy and movement in production. These acts of remembrance are the unplanned surplus of colonial capitalism, the excess actions unaccounted for in the in the development of industry and its subjects. [11]

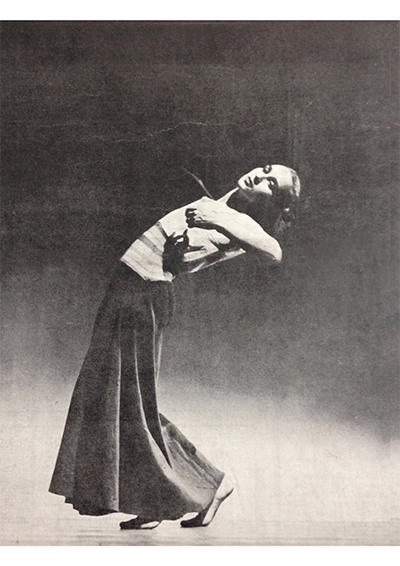

Figure 3) Anna Sokolow on the cover of Dance Observer, Vol. V, No.3 (March 1938). Photo: W.M Stone.

The histories of the contexts that Sokolow calls upon are plucked from the overwhelming weight of the past as an act of piecemeal intervention, selected and remembered as fragments in the performative mode of dance as it intersects with poetry, music and readings. The insistence of this overlaying – dance presented at once with these other descriptive forms – evokes a particular physicality in the act of remembrance, a forceful and evident conjunction of history and movement.

Presented sequentially, like the chapters of a book, or the array of stories in a newspaper, the women’s bodies move in conjecture with the recollection of abridged histories. Their disciplined movements, learned together, through practice and repetition speaking of the necessity of tactility and movement in the process of learning, the process of reading, the process of recalling. Even before the tactility of the objects themselves – turning the pages of the book, thumbing the newspaper – there is the tactility of learning to read, of learning to listen, of learning to recall and represent the past, always done between bodies, passed between them, as a repetitive, caring action. Movement, then, is a locus of remembrance; a sensitive and on-going process of training: a labour of sociality...

...but this materiality of knowledge and technique as embodied processes, again, is always bound to transition: the labour of care becoming a labour of war; an act of nurture becoming an expression of violence; structure becoming ruined; the very act of remembrance itself always complicit with forgetting, whether forceful or accidental.

Disjointed and fragmentary, A Strange American Funeral does not offer the viewer a stable centre or a calm, graceful space of retreat, but rather, displays the body as a complex and abstract mechanism that is joined to a network of processes, behaviours, histories and geographies. Through tics and stutters these dances demonstrate that tools, transit, infrastructure and war are not external to the body, but rather, are embedded in flesh by way of gesture and repetition. [12]

2015

The floor and the walls of the MoMA’s 4th floor lobby are clean and white. Rectangular floodlights line its perimeter on three sides, angled upward to produce dramatic shadows. Selling out quickly, On the Concept of Dust (2015) (Rainer’s first live performance at the MoMA), was eagerly anticipated. As the audience arrived they were given a reading assignment, which was handed out alongside the official programme notes.

Entering flanked by her dancers, Rainer performs a brief solo, which prompts the pianist who is installed on stage right to begin playing. Rainer’s favourite work in the MoMA’s collection, Henri Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy (1897) has been de-installed from the fifth-floor galleries and placed behind the performers, protected by two art handlers who will slowly roll it out of view over the course of the dance.

Figure 4) Yvonne Rainer. The Concept of Dust, or How do you look when there’s nothing left to move? 2015. Performers, from left: Keith Sabado, Patricia Hoffbauer, Yvonne Rainer, Emmanuèlle Phuon, David Thomson, and Pat Catterson. Photograph © 2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Dressed in sneakers and slack clothing, the dancers shoes squeak on the shiny floor, creating similar acoustics to a basketball game. There are snippets of Rainer’s iconic choreography, like the interlacing paths of pedestrian jogging shooting diagonally across the performance space. During the warm-up, a dancer stands in quiet profile with bent knees and arms swinging from side-to-side, the opening movement from Rainer’s Trio A. These well known phrases give way to more showy routines: snaps, jazz hands, and a fan kick, juxtaposing her well known utilitarian style with high camp show pieces, inter-splicing and relating the two styles. An ungraceful waddle takes the dancers off the floor and upstage, followed by a comic wiggle of an imaginary doorknob, and an earnest wave of greeting that brings them back to centre stage. Dancers take turns leaving and returning to one another, all these sequences are interrupted and overlaid by Rainer’s narration, speaking of the history of Islam, a hedgehog’s ancient fossil and the Middle East.

Rainer leaves her post on a chair to the stage left to chase dancers around the floor, pushing the microphone into their face, forcing them to read from her script, exaggerating her directorial mode.

In the background Gavin Bryars The Sinking of the Titanic (1969) is playing. First recorded in 1975 on Brian Eno’s Obscure Records, its title is a reminder of an American disaster: a disaster of engineering, of transportation, of expertise. Bryar’s composition draws from a Christian hymn played by the RMS Titanic’s band. They were playing as the ship went down.

Catastrophe laces the performance: the hand-outs given to the audience concludes with Frederic Jameson’s assertion that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. The audience sits with this note in their hands or under their chairs: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. The dance finishes, the painting and the performers have exited the floor. The audience leaves.

[1] Elie Siegmeister composed a score based on Gold’s original poem and not specifically for Sokolow A Strange American Funeral. Sokolow contacted Siegmeister to ask if he would like to be involved in the performance on hearing his composition. For additional information on Siegmeister’s involvement with composition for dance see his “Music for Dance” in New Theatre, vol 11., no. 10 (October 1935), pp.12-14. Available via the Laban Library & Archive, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London.

[2] Gold, “Michael A Strange American Funeral at Braddock (1924)” New Masses, Vol. 18 (June 1942), pp.25.

[3] The language of the poem contrasts the softness of Clepak’s lived life - his walks to work through the Pennsylvania spring, his wife’s breasts, his child’s lips – with the coldness and hardness of the steel factory, the institution through which his labour was objectified and his personhood extinguished. Clepak’s brutal death is cultivated in Gold’s poem to become the ultimate metaphor for the conditions of the industrial worker: a people subjugated to the extent that their bodies are totally absorbed by the industrial process. The horror of such a movement, from person to thing, becomes the rallying call with which Gold incites action. Speaking through an imagined comrade of Jan’s, Gold states: “”I’ll come some day and make bullets out of Jan’s body, and shoot them into the tyrant’s heart!”[3] Clepak’s flesh then is not lost to the factory, but is metaphorically recuperated and weponsied for the workers struggle. Gold, Michael A Strange American Funeral at Braddock (1924).

[4] Graff, Ellen Stepping Left, Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928-1942 (Duke University Press: Durham, 1997) pp.184.

[5] Rukeyser, Muriel “Review of the Dance Festival” New Theatre Vol. 11, No.8 (August 1935), pp.33. Available via the Laban Library & Archive, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London.

[6] Leonard Dal Negro noted his 1935 review of the performance in the New Theatre, presented “sharply stylized [and] aggressive [movements]…designed free and independent” of the formal dictates of its theatrical accompaniments. Dal Negro, Leonard “The Dance Unit” New Theatre Vol. 11, No.8 (August 1935), pp.22-23. Available via the Laban Library & Archive, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London.

[7] Dal Negro, Leonard “The Dance Unit” New Theatre Vol. 11, No.8 (August 1935), pp.22-23. Available via the Laban Library & Archive, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London.

[8] Dal Negro, Leonard “The Dance Unit”, pp.23.

[9] John Martin noted in his review of Strange American Funeral that: “[t]he problem of building dance forms on verbal forms is still far from solution and the Siegmeister music further complicates matters by making the poem unintelligible. Nevertheless there are powerful phrases in the dance, and much of it is original and compelling.” Martin, John “New Dance League Holds 3d Festival”, New York Times, June 10, 1935.

[10] Programme notes from Anna Sokolow and Dance Unit performance, (undated) in Joseph North and Helen Oken North Family Papers: Series I: Joseph and Helen Oken North Papers (Records and Memorabilia), Anna Sokolow Posters and Programs (Undated) Tamiment Library & Wagner Labor Archives, TAM.605, Box: 8, Folder: 14., New York University, New York.

[11] Kluge, Alexander and Negt, Oskar History and Obstinacy, Chapter One.

[12] Ibid.